How Do You Know?

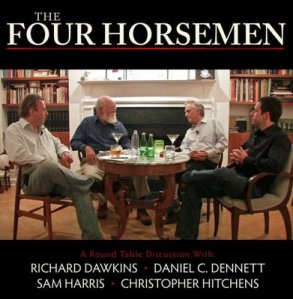

This weekend, a friend alerted me to an interesting DVD special where four of the more prominent atheists out there right now (Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, and Sam Harris) get together for a round-table discussion. The two hour unmoderated discussion is, interestingly, entitled “The Four Horsemen“—a reference, presumably, to the protagonists’ understanding of themselves as the agents entrusted with the hastening of the demise of the blight upon human history that is religion.

From the bit that I watched, the special seems to be mainly about these four guys sitting around congratulating themselves on the obvious superiority of their views, ridiculing religious people, and sharing stories about the “persecution” they’ve experienced from those who have not yet attained their level of intellectual development. I watched twenty minutes or so of the first hour on YouTube and found it fairly uninteresting—mostly, I presume, because I’ve read each of their books and they don’t really say anything in their discussion that they don’t say in their published works.

One part that did interest me, however, was near the end of the first hour when Sam Harris asked his fellow atheists if they had ever come across an argument that gave them pause, that planted even the smallest seed of doubt in their minds that their militant assault on religion might be misguided. For the most part, they said that they could not. Dennett just bluntly said “no”; Dawkins and Hitchens said something to the effect that they sometimes wondered about the political ramifications of angering religious groups, but not one of them claimed to have ever come across an actual argument that wobbled the foundations of their atheism in any way. One gets the sense that it is literally beyond their capacity to imagine how or why any intelligent person could possibly not see thing the way they do.

The new atheists are frequently accused of a rather breathtaking and condescending form of arrogance in claiming to understand and diagnose the “disease” that is religion, but for me, their arrogance is most obvious in their implicit view of the history of human thought and experience. They really do portray themselves as representing the absolute pinnacle of human intellectual development; they, alone, occupy the privileged position of surveying the human condition with absolute clarity, free from the superstitious fantasies that have clouded the judgment of the overwhelming majority of human beings who have ever inhabited the planet.

C.S. Lewis once said that one of the things he found most troubling as an atheist was the view he was forced to take with respect to how others think. In Mere Christianity, he says:

If you are an atheist you do have to believe that the main point in all the religions of the whole world is simply one huge mistake. If you are a Christian, you are free to think that all these religions, even the queerest ones, contain at least some hint of the truth. When I was an atheist I had to try to persuade myself that most of the human race have always been wrong about the question that mattered to them most; when I became a Christian I was able to take a more liberal view.

The “Four Horsemen,” it seems, have no such misgivings. They simply know the truth; the only issue is how to break the news to the rest of us—how to relieve us of our delusions in the most painless manner and avoid stoking the flames of religiously-fueled violence.

In each of the new atheists’ books that I’ve read, the author expresses astonishment at how religious people can claim to have certainty about their beliefs. After reading their books, observing a few of them in debates, and now my brief exposure to their discussion amongst themselves, I can only wonder where the epistemological humility they plead for from religious folks is. John Stackhouse, in a word of warning to those tempted toward claims of certainty in the arena of faith, has recently posted on the importance of recognizing the epistemic limitations faced by all human beings, religious or not. Here’s a summary passage:

This is, finally, the point of it all. We Christians “live by faith, not by sight” (2 Corinthians 5:7)—and so does everybody else, actually, since no human being can transcend our common situation of epistemic finitude. In fact, if we enjoyed all the certainty (in the former sense) that some Christians say we should claim, well, then, we wouldn’t need faith anymore. We would just know things, and we would know that we were entirely right about them.

I think that a little more humility would be a very good thing, on both sides of the atheist/theist divide. We simply are not the sort of creatures who can know, with 100% certainty, that we are right—especially when it comes to metaphysical questions of meaning and purpose. A kind of “fortress mentality” is as evident in “The Four Horsemen” as it is in the most dogmatic circles of religious fundamentalism. In response to the ambiguities and complexities of the real world, both retreat to the safety of certainty, simply declaring (louder and more angrily if necessary) that they are right and everyone else is wrong.

The problem is that the certainty being sought and claimed (on both sides) is illusory. As Stackhouse reminds us, it simply is not possible to transcend the inherent limitations of being human. A wider appreciation of this truth could lead to the welcome recognition that conviction and commitment can be held and articulated humbly and graciously, without demonizing, ridiculing, or questioning the intelligence of those who do not share it.

Discover more from Rumblings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I think Lewis commits an either/or fallacy here. I don’t think its either you are an Atheist who believes that all religion is a huge mistake or you are some sort Theist who thinks thinks there is a grain of truth in other forms of Theism. You state that quite well in your post here. There are Atheists who think that religion promotes myth’s that contain great truths.

Do you think that certainty equals arrogance and that if someone is certain about their beliefs being true that makes them false? I would think that if Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris, and Dennet are wrong… it has nothing to do with their real or perceived arrogance.

Part of the trouble with the N.A. crew is that they are stuck inside what Charles Taylor has called a “subtraction account” of secularization. There is a reductive and facile side to their arrogance. The presumption is simply that if we “subtract” things like religious belief and practice, getting such superfluous accretions out of the way, then we’d get down to what “really” is human (which just so happens to be secular). This looks like an argument, but it’s little more than a presupposition to be able to see (better than everyone else) what the genuine essence of human-ness is, subsequently dressed up with a quasi-historical narrative about the march of progress.

It’s genuinely silly to pretend to be able to say absolutely, “x is a part of what it means to be human, and y is merely a superfluous addition.” History is the story of a huge range of possibilities for different ways of structuring human lives and societies. All of them made sense to the people who inhabited them. Of course we can, and should, talk about which ways of living as human beings are better or worse than others. But there is no universally accessible absolute here that is capable of verification through “empirical evidence” (as if anyone was capable of standing back from “human-ness” far enough to be able to see it plainly).

What we do have is testimony and conversation; and we can and should make our cases for the relatively best way of understanding ourselves and our world. There is, however, no “neutral” ground in the conversation.

Ryan, those fellas just haven’t had access to your thesis yet!

JC,

Most atheists seem to recognize that there has to be some kind of naturalistic explanation for the ‘religious impulse,’ some kind of explanation for the fact that most people believe in something that does not and never has existed.

So if you want to follow atheistic assumptions to their logical end you have to conclude that most human beings, throughout most of history have been wrong about what, as Lewis says, matters most to them. So I’m not sure I see the fallacy in the quote above.

Even if you come to the conclusion that there are ‘necessary myths’ in some religions, there is still the implied belief that basic religious convictions are wrong, no matter how generous a conclusion you come to regarding their usefulness.

jc, other than echoing what Gil said about the Lewis quote, I would simply add that I do not think that certainty in general equals arrogance. But as I said in the post, I don’t think either side can claim certainty in this matter. Of course the arrogance of the new atheists doesn’t make them wrong, but it certainly doesn’t do much to promote genuine dialogue.

Eric, thanks for bringing Taylor into the discussion. I’ve still yet to complete that book, but so far I’ve found his account of secularization to be a pretty compelling (and comprehensive!) one. His “subtraction account” of secularization seems pretty much in keeping with Dawkins’s view that history is the story of getting rid of gods (just one more left to go for the monotheists).

Dave, yes I’m sure that Dawkins & co. (like countless others, no doubt) are eagerly awaiting the flood of illumination that will enter the world with the completion of my thesis…

Yeah… right.

Gil,

I guess I didn’t really consider what Lewis thought was basic. I suppose the basic hint of truth is that there is a supernatural realm? That would leave out a lot of very basic beliefs of Christianity that I might have wrongly assumed were basic beliefs. I believe I see the point now but please correct me if I am wrong about it.

I didn’t realize that most Atheists thought it necessary to explain a religious impulse. I am not sure whether Atheist’s wish to explain the psychology of religious belief because they want to discount though the explanation or they think that the phenomenon is so pervasive that it demands an explanation.

What is Lewis argument here in the quote?

Is it

If God does not exist then a lot of people in this world are going to be wrong. It is more liberal to believe that a lot of people are right about there belief in God.

So I choose to believe God exists.

or is it

If God does not happen to exist then a lot of people are wrong. A lot of people can’t be wrong such an important belief so God has to exist.

I haven’t read everything written by the FOUR, but I get the impression (so far) that if religion died out or never existed, and the worldviews the FOUR considered to be the most probable realities (among many other probable realities around the globe)…

..these worldviews of theirs (and all others in the past), even though they were what “matters most to them”, could be deemed ridiculous and unintelligent by their own judgment if the FOUR were capable of having demonstrated to them in the distant future far more probable worldviews.

(Sorry for the run-on sentences.)

I have to confess, evidence of the natural versus no evidence of the supernatural have made atheists such as myself a little too confident – not exactly discussion friendly;)

I just read the Stackhouse post. The paragraph that I found interesting is…

“So I think it’s fine to say that I am “certain” about these things. When I do, I am reporting on my state of mind. I am saying that I am so highly convinced of them that I entertain no serious doubts about them. I think, and feel, and act with untroubled confidence in them.”

I wonder if the FOUR would say this describes their confidence.

JC,

My understanding of Lewis’ argument is that if you want to follow atheism to its logical conclusion, you have to say that the vast majority of human beings that have walked the earth have been mistaken about reality. He’s not referring only to Christians here but all those who hold some kind of belief in what you call the supernatural realm.

This is why many atheists (at least the ones writing the books) feel like there must be some explanation for why we as a race could have been so wrong for so long.

Atheists are forced to say that every religious person is wrong about what they think is most basic to reality (even if they would be reluctant to say it that way, even if they think religion has psychological or social benefits).

That is a different perspective than what Lewis calls the ‘more liberal view’ that religious believers can take with one another. Even if there is disagreement on God (or the gods) there is still agreement around the idea that there is more to reality than a naturalist worldview would allow.

jc,

Just to add one thing to what Gil said, I don’t think that Lewis is making an argument for the existence of God in the quote I cited. He’s simply reflecting upon his own psychology as an atheist vs. as a Christian, and saying that one of the benefits of being a Christian is that you do not have to write off a substantial component of the history of human thought as completely mistaken. I think he would be the first to admit that this doesn’t prove anything one way or the other about God’s existence.

Jerry,

This is certainly what Dawkins seems to think – that every intelligent person who existed prior to Darwin was some kind of a latent atheist who would have gleefully and gratefully sloughed off their belief in God once presented with the wonders of modern science. Of course the subsequent development of human thought would seem to challenge this. Many people seem quite capable of accepting the deliverances of modern science and retaining their belief in God.

Well, as we’ve discussed many times in the past, this is to assume that only one kind of evidence (physical evidence) is admissible in discussions of metaphysical questions. This seems like an odd requirement to me. It’s not like we moderns are the first people to discover that God isn’t an observable piece of data in the physical world.

The Stackhouse quote you cited would undoubtedly describe the confidence the “Four Horsemen” have in their views. The problem is they rarely present themselves in such measured and civilized terms. More often, the rhetoric is, as I said in the post, that everyone who doesn’t see the obvious truth that they possess is some combination of willfully ignorant, indoctrinated, intellectually dishonest, fearful, etc. It’s one thing to be confident in one’s views (I certainly am); it’s another thing entirely to present yourself in such a way as to alienate and antagonize those you claim to be attempting to engage in dialogue.

I’m not sure, but I think you might have misunderstood my run-on sentences. What I meant was that the FOUR consider it quite likely that the way they treat religious theories of others is a way they would treat their current theories after receiving far better ones. (I don’t know if this clears things up or not.)

“It’s not like we moderns are the first people to discover that God isn’t an observable piece of data in the physical world.”

Are we only talking about a Deist’s version of “God” here? Because I thought any other version of “God” would include natural phenomenon as empirical evidence of supernatural causes.

“It’s one thing to be confident in one’s views (I certainly am); it’s another thing entirely to present yourself in such a way as to alienate and antagonize those you claim to be attempting to engage in dialogue.”

There certainly is a good portion of goading in their comments about Christianity. I think they know they’re alienating many, but I also think the goading is motivated by a desire to get people like yourself to justify religion rationally.

I wish there were more of us who try to find rational justifications for religion, believers and non-believers alike. I think there are alot of misunderstandings of people’s religious beliefs (including those who believe them). And I think the world has alot to learn about itself in this area.

The work of theology may be slammed for various reasons, but whether it’s a revelation of God’s identity or not, any change in one’s theology is a change in the person – in this sense, I think theology can be extremely valuable.

I think I’m getting off topic here… I hope you don’t mind if I just leave what I’ve written above.

Thanks for the clarification. This still seems to presuppose a very specific view of human thought – that it is a one-way street of improvement. It also seems to presuppose that religion is a kind of primitive version of scientific rationality – that, for example, atheism is to religion as neuroscience is to phrenology. There are obviously many (myself among them) who would question the assumption that science and religion are simply competitors for the same “explanatory slot” and that the advance of one means the retreat of the other.

I wasn’t talking about a deistic God, although I think deists would be as keen to include natural phenomena as evidence for the existence of God as anyone else. There is obviously a broad spectrum of beliefs regarding what the natural world says about God, or how prominent a role it ought to play in discussion about the question of God’s existence.

I brought up the idea that people have known that God wasn’t an observable piece of data for a long time in response to your claim that we have “evidence of the natural versus no evidence of the supernatural.” I understood you to be saying that the lack of a specific kind of evidence (physical) was what accounted for your confidence in atheism, which is why I brought up the fact that evidence comes in a variety of forms – especially when we wander into the realm of metaphysics (of the theistic or atheistic variety).

That may be part of the FOUR’S motivation but as I said in the initial post I think that their response, like other religious fundamentalists, is also motivated by fear. Our world is a complex and morally ambiguous one and the temptation is often to default to simplistic, binary answers (religion = bad; atheism = good) and an imagined certainty that simply does not exist.

I don’t think that I, or anyone else, have to “justify” religion rationally. I think that I have sufficient warrant to believe, but I’m not convinced that reason is the ultimate standard by which all things must be measured. A lot of pretty awful things have historically been (and undoubtedly will continue to be) “justified” by reason.

“There are obviously many (myself among them) who would question the assumption that science and religion are simply competitors for the same “explanatory slot” and that the advance of one means the retreat of the other.”

I think it’s more likely that the supernatural and the natural are competitors for the same explanatory slot.

Religion has far too many naturalist qualities to say otherwise.

Anthropologists and historians have plenty of material to provide examples of scientific explanations replacing supernatural ones. Not to mention Creationists’ arguments for irreducible complexities.

“religion = bad; atheism = good”

I don’t think this is a proper representation of what the FOUR have communicated, either. If they chose a “binary answer” I would expect to hear them say, ‘irrationality = bad; rationality = good’. Which leads me to your last words…

“I’m not convinced that reason is the ultimate standard by which all things must be measured. A lot of pretty awful things have historically been (and undoubtedly will continue to be) “justified” by reason.”

Reason is it’s own competitor, able to be used as a valuable tool to correct any conclusion arrived at with a previous use of reason. And so, yes, awful things can be justified by reason. But how do you see belief in supernatural revelations as a more reliable method to avoid justifying awful things in the past and present?

When you put supernatural revelation and natural reason together, which one has had a greater positive influence on the other for humanity? (What would theologians and biblical scholars be without reason?)

Which method do you prefer over the other, Ryan: faith in faith (the kind of hope that can make anything seem true) or faith in reason (the kind of hope that can actively challenge and correct an unreasonable amount, or kind, of faith put into previous uses of reason)?

Whether you want to use the terms natural/supernatural, science/religion, or rational/irrational, you still seem committed to a construal of all human history as a straightforward linear progression from darkness to light. The actual development of history is a little more complex than that.

Well, based on the reading I’ve done, I would disagree – especially since for them, irrationality = religious and rationality = atheism. Saying that religion “poisons everything,” for example, doesn’t leave a whole lot of room for ambiguity. Dennett might have a bit more of a nuanced account of things, but certainly Dawkins, Hitchens, and Harris are pretty clear about this.

No question. Supernatural revelation, hands down. (I think the way you’ve put the question represents a false dichotomy, but if that’s the way the question is put to me, that’s how I’ll answer it.)

Where would modern scientists and natural philosophers be without the cultural framework and theological assumptions which made scientific investigation of the natural world seem plausible?

Where have I ever said that I have “faith in faith (the kind of hope that can make anything seem true)?” This is another false dichotomy.