Love for the Incorrigible

I’ve been slowly making my way through Marilynne Robinson’s beautiful commentary on Genesis. It’s called, simply, Reading Genesis, and those who know anything about Robinson or her work will not be surprised to learn that it reads rather differently than a typical biblical commentary. Her soaring prose, her seemingly effortless command of complex biblical, historical, and philosophical issues, and the ways in which she weaves all this together in conversation with an ancient text is marvellous to behold.

The story of the flood (Gen. 6-9) obviously raises all kinds of issues for modern readers. Yes, it’s a story that captures the imaginations of young and old. Noah and his floating zoo provide the imagery for children’s nursery murals and storybooks, and the brilliant colours of the rainbow speak to the hope of a world renewed, cleansed, purified. But obviously the much darker subtext is that this is a story of human depravity and divine judgment. Human beings have grown so wicked that God is sorry he ever made them. The flood, far from a pleasant kids’ story, can quite easily be read as the retributive blast of a vengeful God.

Throughout Reading Genesis, Robinson acknowledges that the stories can seem morally problematic. Yet through reading Genesis in conversation with other ancient Near Eastern stories (and noting how they differ), and through a creative reading of the text itself, she reframes them in helpful ways. It’s relatively easy to read the story of the flood as the story of an angry God wiping out his wicked subjects (not so different from other ancient deities). But, Robinson asks, what if we read the story as a literary device called an inclusio, where the story is meant to be bracketed by two statements about God’s disposition toward his creation.

Genesis 6:5-6: The Lord saw that the wickedness of humankind was great in the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually. And the Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.

Genesis 8:21: And when the Lord smelt the pleasing odour, the Lord said in his heart, ‘I will never again curse the ground because of humankind, for the inclination of the human heart is evil from youth; nor will I ever again destroy every living creature as I have done.

Robinson ponders the distance between these two divine dispositions, between God’s grief at human wickedness that preceded the flood and the promise that followed:

What has happened between the first and the second of these thoughts in the heart of God? Noah and his family have waited out the Flood, left the ark when they could, and… offered fragrant sacrifices. The Lord “smelled a sweet savour,” as the pagan gods do. The sacrifice might mollify Him in some way, because Noah has hoped to restore a bond of experience between God and man. But something much deeper has happened. The Lord, in the thoughts of His heart, has yielded to His love for the incorrigible—in Old Testament terms, His Absalom; in New Testament terms, the Prodigal; in theological terms, the lot of us.

On a literal reading of Genesis 6-9, the flood didn’t work. It didn’t fix anything. The reboot did not lead to a purified, cleansed, chastened humanity. Human wickedness remained. But perhaps the story is meant to tell us more about God than about us. Perhaps, Robinson says, it is meant to reveal the ways in which this God different from all the pagan gods of the time. It’s hard to imagine any of the gods of the Ancient Near East yielding to anything like their “love for the incorrigible.” This was (and remains) an utterly unique disposition in the religious landscape. It’s fascinating to read the story of the flood in this way—as God sort of giving in to his own love for all the Absaloms and prodigals out there blundering their way to ruin and back.

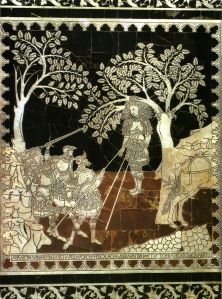

Speaking of Absalom, I spent some time reading his story in 2 Samuel today. It’s pretty grim reading, full of rape and violence and treachery and rebellion against his father, King David. In the end, Absalom famously gets his hair caught in a tree while fleeing his father’s army on horseback. He hangs there, pitifully, before he is finished off by a handful of the captain Joab’s armour bearers. When David hears of his son’s death—the son who betrayed and humiliated and rejected him in countless ways, the son who would have seized his throne, he weeps. And he speaks the famous words that have echoed down through the ages:

O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would that I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!’

This is, of course, a kind of prefiguring of what God himself, in Christ, would do for all his incorrigible sons and daughters. On Calvary’s cross, of course, we see Jesus enacting David’s cry. Dying in the place of his rebellious children, giving himself up for the very ones seeking to refuse and reject his kingdom.

Thank God that God yields to his love for the incorrigible. Which is to say, the lot of us.

Discover more from Rumblings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Isn’t absalom in 2 Samuel. Robinson Genesis sounds interesting. Anticipating our Anabaptist Community Bible

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

Yes, 2 Samuel. Change made. Thanks.