I’ve Been a Good Boy!

Among the readings I encountered during morning prayer today was Psalm 17:1-7. It is a plea for divine vindication, protection, blessing, and favour from the pen of David. I have long had something of a complicated relationship with the Psalms. I know that the Psalms are the prayer-book of the church, that really smart and spiritual people pray them every day. And they do express the full range of human emotion. And they do contain some of the most beautiful and exalted language in all of Scripture. But sometimes the implicit theology doesn’t land. It strikes me as true-ish, but not true enough.

I was struck, in today’s reading, by the structure of David’s plea.

Hear a just cause, O Lord; attend to my cry!

Give ear to my prayer from lips free of deceit!

From your presence let my vindication come!

Let your eyes behold the right!

You have tried my heart, you have visited me by night,

you have tested me, and you will find nothing;

I have purposed that my mouth will not transgress.

With regard to the works of man, by the word of your lips

I have avoided the ways of the violent.

My steps have held fast to your paths;

my feet have not slipped.

I call upon you, for you will answer me, O God;

incline your ear to me; hear my words.

Wondrously show your steadfast love,

O Saviour of those who seek refuge

from their adversaries at your right hand.

David’s basic strategy seems to be, “Look, God, I’ve been a very good boy. So please answer me, save me, deliver me.” He helpfully itemizes his merits for God to scrutinize:

- My lips are free of deceit

- You have tested me, you will find nothing

- My mouth will not transgress

- I have avoided the ways of the violent

- My steps have held fast to your paths, my feet have not slipped.

“I think you’ll find, dear God,” David seems to be saying, “that my performance merits a positive response.” Now this conditional formula doesn’t come out of nowhere, clearly. Deuteronomy 28 is perhaps the most well-known example of tying blessings to obedience and curses to disobedience in a straightforward if/then way, but examples can be found throughout Scripture. David isn’t making this idea up out of thin air. He has at least some grounds for thinking that God will respond positively to human virtue and fidelity.

The problem with his approach, theologically, is rather obvious and is twofold in nature. First, righteousness (in Scripture and in observable reality) does not always correspond to deliverance or blessing or rescue. Good, moral people suffer incredibly. All the time. There’s Jesus, obviously. Less impressively, there’s the disciples whose lives were generally short and full of trials of all kinds. There are countless saints down through the ages who were familiar with pain, whose enemies at least seemed to triumph over them, whose prayers were not answered in the ways they hoped. I suspect we can all think of fairly admirable people in our lives who have gone through things that would seem rather unfair, were blessings meted out straightforwardly for moral performance.

And then there’s the problem of just how good our performance actually is. I suspect a few readers were kind of coughing and ahem-ing through David’s recitation of his qualities. “You will find nothing?” Really? No deceit or transgression? No violence? No wandering off the straight and narrow, no moral slippage? Which David, exactly, are we talking about here? Even those with a passing familiarity with his story could likely come up with a few pieces of evidence that might call into question David’s self-assessment here. David is, like so many of us, rather prone to overestimating his good deeds and under-reporting that which is less flattering. At least in this psalm (Psalm 51 is the necessary counterpoint here).

In very general terms, I think the reason passages like Psalm 17 land only as true-ish is because they only tell part of the story. And not the deepest part. Yes, in very general terms, it’s better to be good than bad. Things will generally go better for you in the world. And God is certainly more pleased with righteousness than wickedness! But the gospel is not a moral formula. The far deeper truth of the gospel is not that God offers love and salvation as a reward for good human performance, but as a response to its absence.

The hope of the gospel is that Christ died for and offers salvation to the poor performers. Romans 5:6-8 sums it up:

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. Indeed, rarely will anyone die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person someone might actually dare to die. But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us.

I am struck by the deep truth of this during prayer time every Monday at the jail. These guys can’t really say, “Look, God, I’ve been a very good boy, how about some rescue?” They are confronted in a visceral way by a painful and universal truth. We are sinners in desperate need not of a moral calculation, but of grace. All they can say is all any of us should ever have to say, what the tax collector in Luke 18 had to say: “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” This, Jesus says, not a recitation of our merits (as the Pharisee was busying himself with in the other corner) is what sends us home justified. Perhaps a more Jesus-y psalm would be, “My cause isn’t just. I’ve been a pretty terrible boy, truth be told. Please hear my cry for mercy.”

Well, speaking of the Psalms and how they don’t always land, I need to also say that sometimes they absolutely do. I read a portion of Psalm 139 at a graveside of a young woman last week. It was a story soaked in pain and sorrow and sin and struggle. It was among the more difficult graveside services I have ever done. Psalm 139 is a prayer to the inescapable God, the God who hunts us down in dark places, who refuses to leave us alone:

Where can I go from your Spirit?

Where can I flee from your presence?

If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast.If I say, “Surely the darkness will hide me

and the light become night around me,”

even the darkness will not be dark to you;

the night will shine like the day,

for darkness is as light to you.

This is the truest, deepest, most profound hope: our darkness is no match for the God of heaven and earth. We cannot flee from the presence of the God whose mercy is more stubborn that even our sin. Our goodness and our badness will ultimately by overwhelmed—judged, exposed, relativized, forgiven, and forgotten—by the One who is light and life.

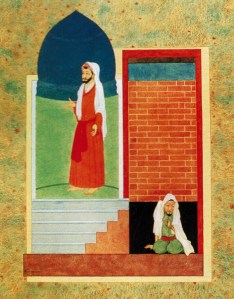

Image source.

Discover more from Rumblings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.