Here We Are Now, Entertain (or Train) Us!

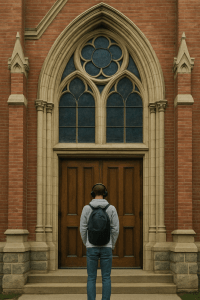

Apparently, the kids are turning back to Jesus. That’s a bit of an overstatement, perhaps. We’re not talking about Jesus People 2.0 or mass waves of feverish Pentecostal revivalism (at least not yet). But the data does seem to point to a significant trend. According to a recent Barna survey, Gen Z and Millennials are driving a significant return to Christianity in America (around 10-15 percentage points from 2019 to 2025). A British study pointed to a similar trend, noting that “the proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds who attend church at least monthly has risen from 4% in 2018 to 16% in 2024.” No, the overall numbers are not huge and, yes, statistics and surveys are malleable, but still. Something does seem to be afoot.

The reasons for this trend are likely many and varied. The pandemic and its discontents almost certainly played a role. The social and political chaos of our cultural moment would factor in. The bleak economic conditions and the paucity of optimism for the future, certainly. The desolate wasteland of the internet and how it is corroding our discourse and our selves. And there are, of course, undeniable existential itches that do demand to be scratched, at least at some point in every human life.

But perhaps this Gen Z/Millennial trend also has something to with who their parents were. This is the interesting thesis of a piece called “The Age of Nihilism is Over” by Mary Harrington. Gen Z and, perhaps to a lesser extent, Millennials were raised by Gen Xers who kind of gloried in the meaninglessness of life. We were the generation raised on Nirvana (“Here we are now, entertain us!”) and nihilism. What is truth? Who can say? Who cares?

Harrington (herself a Gen Xer) puts it like this:

Either way, by the time I reached adolescence in the early Nineties, there didn’t seem much left to believe in; and yet, growing up in an unusually peaceful and prosperous era, we combined this sense of post-cultural anomie with far too much time to think.

As a fellow Gen Xer, I remember this feeling well. I marinated in the grunge music of the 90s, and even if I didn’t go all in on the nihilism, I certainly felt it in the world around me. Meaning was precarious, at best. Religion was scorned. Apathy was a badge of honour; detachment was a duty. It all felt so very cool and countercultural. And did I mention the how good the music was? I can’t help but chuckle at the sight of 18-year-olds walking around with Pearl Jam and Nirvana t-shirts these days. At least they’re getting one thing right. If they’re even listening, that is…

I digress. Harrington interrogates the trickle back to religion among the young through the lens of Gen X’s approach to life and parenting. She asks a question the implications of which, in my view, reverberate around the post-Christian West:

But what happens, then, when nihilists have kids? Raising kids requires innumerable choices, all of which tacitly concede a vision of the good.

So many things that we do require tacit concessions of some vision of the good, don’t they? We may be loath to admit it, we may prefer to imagine ourselves as courageous nihilists or postmodernists or anarchists or libertarians or whatever, but once we bring another life into the world, we sort of have an obligation to steer them in a concrete direction. It’s hard to train up a little nihilist without driving yourself a bit crazy and tying yourself in all kinds of intellectual knots. Why subject this precious little creature to a world of meaninglessness and suffering? Is nihilism normative? Is that even possible? Should you care? Parenting requires a bit of moral renegotiation of one’s commitments. Or at least it should.

Many Gen X parents took the path of least resistance. They raised their kids in a kind of default, benign, vaguely Christian ethic (be good, be kind, etc.) and said, explicitly or implicitly, “You decide what works for you when it comes to the big questions.” I have seen this so often as a pastor. Parents imagine that they are doing their kids some kind of heroic favour by refusing to sway their children by their views on existential questions like, “What is the meaning of life? What should I pursue? Is this life all there is? Etc.). “Just be true to yourself” sounds so much more enlightened and tolerant than imposing our views on our kids, right?!

Well, maybe not. Maybe the kids wanted, even needed more than their Gen X parents had to offer (or were comfortable offering). Maybe they wanted someone to help them know what to think, how to know what was right and wrong, what they ought to give their lives to. Maybe we assumed that they were as eager for freedom as we were when in fact what they wanted was a few guardrails. Maybe what we experienced as liberation (just do whatever you want, whatever makes you feel good) they experience as oppressive. Maybe they don’t want to make everything up for themselves.

And from a church perspective, maybe the very churches that chased after relevance and cultural acceptability ended up becoming irrelevant to the very generation they so desperately wanted to bring back. Harrington is speaking specifically of the Church of England here, but I think her words could apply to many more mainline denominations (including the one in which I serve):

In fulfilling its duty as far as possible to offer spiritual welcome to the whole national community, our established Church risks appearing to stand for nothing much, or at best to embody the Christian equivalent of the moral vacuum Wiseman describes. Against this, young people weary of the effort to define their own values and happiness ex nihilo, and eager for guidance from somewhere — anywhere — might be forgiven for concluding that such direction is not to be found in a church whose leaders shrug at turning over their sacred buildings to silent discos or helter-skelters. Confronted by what looks overwhelmingly like a mass abdication of moral authority by parents and religious institutions, then, perhaps the last form of youthful revolt available is against nothingness itself: a rejection of relativism, and embrace of doctrine and mystery.

So much to ponder in all this, at least for this Gen X pastor and parent. I’m reminded of what the historian Tom Holland once said when asked what his advice would be to the church of the twenty-first century:

Churches cannot afford to be a kind of pale simulacrum of secular liberal society. They have to actually emphasize everything that may make them feel embarrassed in a liberal secular society. They have to emphasize the strangeness, the weirdness, the bizarre quality of what they believe in. Because ultimately [Christianity] is weird, bizarre and strange. But it’s that strangeness that has animated it for two thousand years… My advice, for what it’s worth, would be that churches should be prepared to emphasize the strangeness because that is what I think people will be looking for.

Good words for this week of all weeks. The strangest, weirdest, most scandalously embarrassing week of the Christian year. And also, the holiest, most shatteringly hopeful week. The death of God and the staggering hope of resurrection. May we proclaim it with boldness. It’s what the kids (and all of us) need to hear.

Discover more from Rumblings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.